"Objective" application of rules and laws or situational ethics?

universalism and particularlism

Without a frame of reference, it’s hard to know what we’re looking at, it’s hard to know others or ourselves. One of the keys for growth as a person who is able to accept, understand and relate well to culturally different others is the self-awareness and other awareness that comes through having a framework for understanding how cultures differ. Which is the point of this reflection (highlighting one aspect of such a framework).

Let me share some scenarios with you…

Once when visiting a local friend in the Middle Eastern country where we were living, the friend got in a small fender bender. As I observed what happened, I thought my friend was at fault (that was my “objective” perspective). But when he and the other driver jumped out and started yelling at each other, my friend turned to me (a foreign observer, whose perspective would carry weight) and said, “tell him! tell him he’s at fault!” I was suddenly caught between my friendship and my sense of what was “objectively” “true” and “right.” It was very awkward, and hard for me to navigate (I tried to “fudge” or finesse the situation, but my friend was not very happy).

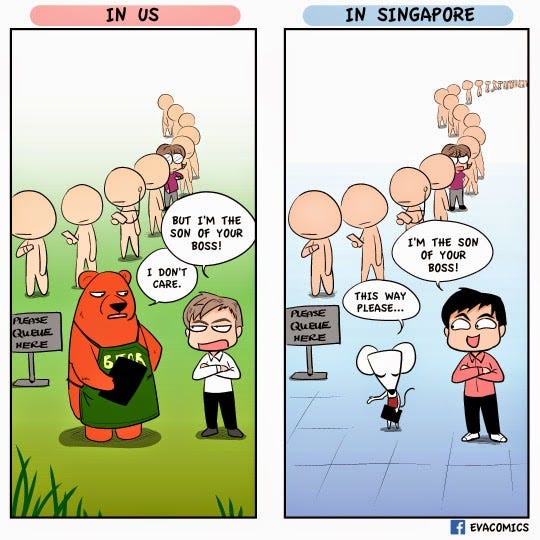

In a different scenario, if someone is pulled over for speeding, should it make a difference to the police officer whether they know the person or not (in terms of whether the officer writes a ticket, gives a warning, etc.)? Or if a business is hiring, should it make a difference whether the applicant for the job is a relative or friend or otherwise known to whoever is doing the hiring?

One of our MESP students, who lives in rural Iowa, said that when he was in high school he was pulled over for speeding on a country road. It turned out the police officer was a member of his church, and knew our student. He let him off with a warning (which was a relief to our student), but then called the father to let him know what had happened (the student said he would have rather had a ticket!).

When I was in college I worked for my father, doing data entry at the Bethel Seminary library. We had statistics for how much data each worker entered per hour, and based on that I asked for a raise (my data entry was twice that of the next highest). I was not asking a favor of my father, but for “just” / “fair” wages. My dad refused, saying he might be accused of nepotism. To which I replied, “I’m a victim of reverse nepotism!”

If you feel that rules and laws should be objectively applied, or that in hiring, the only factor to be taken into consideration should be the person’s qualifications; if you’re upset by the idea of “nepotism” or “preferential” treatment, what’s that about? What does it have to do with culture?

Jump to our time overseas, and consider a number of interesting and sometimes puzzling experiences I had:

Early on in our time in Tunisia, I would go to a local bank to cash a check (the way we got cash in those days!). I got to know one of the tellers. One day I was in the back of a long line, and my teller friend saw me, and indicated that he wanted me to come to him. When I went up to see what he wanted, he asked me for my check to cash. I was surprised, as I was at least 10 people back in line. I said something about that, but he insisted I give him my check, and he served me (ahead of those people), saying “don’t worry about it - it’s ‘normal’.” I felt bad about that (“cutting the line”), but no one in the line protested.

When driving outside of Tunis, we would occasionally be pulled over by police for routine check of car papers (something which happened frequently), or (on a rare occasion!) for speeding. Over time I became aware that the interaction often went like this: the officer said something to me in French (and was not particularly friendly); I responded in Arabic that I don’t speak French; the officer switched to Arabic, smiling and interested, and asked me how I knew Arabic; we talked a bit, and I usually emphasized how much we love Tunisia. Eventually I would ask what I needed to do, and the officer would say “you can go” - without having checked my papers (or one time, without giving me a ticket for being over the speed limit). Once I noticed that this was happening it became a sort of “game” for me - I intentionally sought to engage whoever pulled me over in conversation in Arabic, to see if he would eventually let me go without asking for papers. And we left Tunisia on a “streak” of several years of not showing papers when being pulled over!

Then there was the Tunisia ferry port. We sometimes took our station wagon by ferry to Europe in the summer. When we did, we would always load it up with things we couldn’t get in Tunisia (from IKEA and other stores). The uncomfortable part was the re-entry to Tunisia. When getting off the ferry in La Goulette, the customs officers would require all vehicles to take out all the contents of their trunks for inspection. This was rather a hassle, as it meant a tedious process of repacking the whole vehicle (and the officials were not particularly friendly or nice). But I discovered something interesting: if I jumped out of the car when the inspector came to us, and channeled all my friendliness to engage him in conversation in Arabic about how we love Tunisia, etc., eventually he would ask what we had in our car, and then at most would pull out one bag or item, and let us go! (This friendly engagement became a strategy, and always worked.)

In Jordan one time, we had a group of Bethel University students for a January course. We visited the Roman ruins at Jerash, and then made our way to Ajloun castle. Unfortunately we arrived just as the guard was locking up for the day. We were disappointed. We had some Jordanian friends with us, and one of them said, “just a minute.” He went and talked with the guard, and within 5-10 minutes the gate was reopened, and the guard was personally showing us around! What happened, we asked? Our Jordanian friend found some connection, a close mutual friend or shared relatives or something like that - and that opened the “closed” gate for us!

Another time, we had a work permit denied. Our boss let a friend know. This friend happened to personally know the Minister of Labor (the ministry which issues work permits). We ended up in a meeting in his office, and after an explanation of how vital this work was to Jordan, and why we (the expats being hired) were needed for the company, some new paperwork was initiated, and within the week we had our work permits!

What are these examples all about? What’s going on here? Why does it make a difference to know someone, or have a positive warm interaction with them? What’s the cultural factor at play here?

These examples have to do with one of the dimensions of how cultures differ, referred to as “universalism” at one end of the spectrum, and “particularism” at the other. Some of the characteristics:

Universalism:

There are certain absolutes that apply across the board, regardless of circumstances or the particular situation. What is right is always right. Wherever possible, you should try to apply the same rules to everyone in like situations. To be fair is to treat everyone alike and not make exceptions for family, friends, or members of your ingroup (“nepotism” is definitely not ok). In general, ingroup/outgroup distinctions are minimized. Where possible, you should lay your personal feelings aside and look at situations objectively. While life isn’t necessarily fair, you can make it more fair by treating everyone the same.1

In a cultural context and worldview that leans toward universalism,

The focus is on rules and laws, which should be “objectively” applied across the board.

A deal is a deal, whatever happens.

You don’t compromise on principles.

Consistency is desirable and possible.

Justice is blind (the law should be the same for everyone).2

Reason and logic prevail over feelings.

Exceptions to the rule should be minimized.

Life is neat (as opposed to messy) (you should be able to apply principles across the board).

Northern Europe and the United States (among other places) tend toward universalist culture (but there are exceptions).

Particularism, on the other hand, has the following characteristics:

How you behave in a given situation depends on the circumstances. What is right in one situation may not be right in another. You treat family, friends, and your ingroups the best you can, and you let the rest of the world take care of itself (their ingroups will protect them). One’s ingroups and outgroups are clearly distinguished. There will always be exceptions made for certain people. To be fair is to treat everyone as unique. In any case, no one expects life to be fair. Personal feelings should not be laid aside but rather relied upon.3

In this cultural context and worldview,

The focus is on relationship (rather than abstract rules and laws).

Friends expect preferential treatment; friends protect friends.

Situational ethics prevail (circumstances must be taken into account).

Principles are bent once in a while (you have to make exceptions).

There is a tendency to hire friends and associates.

A deal is a deal, until circumstances change.

The MENA (Middle East North Africa) region tends toward particularism.

One of the things that becomes clear is that universalism tends to correlate with individualist culture (where individuals “stand alone,” “on their own feet,” etc.), and particularism tends to correlate with collectivist culture (in which people are defined by their group membership, the people they are part of).

If you are from a universalist culture, concerned about equal treatment and avoiding nepotism, try to see the perspective of particularists (/collectivists). In a society in which everyone knows each other, it makes sense to work things out relationally. In a tribal village in Jordan, for example, there are no police because they are not needed. Everyone knows each other. When disputes arise, one of the parties brings the issue to the local tribal leader. The leader listens to both parties, and eventually gives a ruling, which everyone considers binding. It’s all based on applying rules / principles / laws to particular people in a particular situation.

In the case of our MESP student in rural Iowa, the police officer, knowing the family and being part of the same church, knew it would be more effective to talk to the father rather than issuing a ticket (with the point being, getting the young person to watch their speed).4 In fact, it often makes a difference in an appearance before a judge in the U.S., for sentencing, whether the guilty party has someone in the local community (a business leader, church leader, etc.) to stand with and vouch for them, and commit to being involved in the person’s rehabilitation or whatever. This is seen (in certain situations) as more effective (toward the goal of stopping illegal behavior) than putting someone in jail.

And in a collectivist society, everyone knows that you can count on relatives and close friends, people who are bound to you socially and therefore committed to you, more than you can count on a random stranger. They think it strange that anyone would even raise a question about this. (It’s one of the reason marrying a cousin is preferred in some societies - you know who you or your son or daughter is joining themself to in marriage, which mitigates the risk of the marriage.)

In fact, a key concept in the MENA region is what is called “wasta” in Jordan (and goes by other names elsewhere). This means someone to “go between” for you (to be in the middle, between two parties), who can open a door for you (to a job, a needed favor, help of some kind, or whatever). This is based on the fact that one of your resources is the network of people you know, and by extension, who they know. Whenever we had an issue of any kind that we needed help with, we would call a local friend to see if they had a friend who could help out. And, by the way, this happens in the universalist U.S., too, right? One of the reasons I got into the grad program I did is because my Anthropology prof at Bethel was friends with an Anthropologist at Brown, where I wanted to study. So the concept is not strange to us. Relationships open doors, even in a more universalist society.

When we were leading MESP, we treated our Program Assistants (we had one each year) particularly, when it came to things like start and finishing dates and time off work. We could do this, because we were a three person staff, and we knew each other well, and our work was relationally based (not based on abstract rules). Particularists would argue that strong relationship is the best foundation for decision making that affects people; that you only need to go by abstract and impersonal rules and laws when you are dealing with so many people that you don’t know what you need to know to treat people according to the particulars of the situation.

And here’s a question to consider, if you are a person or faith: does the Bible, or God, lean more toward universalism or particularism? I think that those of us who are culturally universalist will tend to find universalist perspectives and tendencies in the Bible. We might emphasize laws and rules, principles that God will “hold people to” / judge us by. And that God would of course be fair and impartial (if you can’t count on God to be impartial, what can you count on?).

But then, the Bible seems to be full of examples of God dealing with people very much according to the particulars of who they are, their relationship with God, their situation. Think of God’s interaction with Abraham (a “friend of God”) over the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (Abraham did some Middle Eastern negotiating with God over God’s planned judgment on the towns). Think of God’s relationship with Moses, and the time, for example, when God said he would destroy the people and give Moses different people to lead, but Moses pleaded with God and God yielded. Think of the situation of David and Bathsheba. God did not apply the fullness of the law to David’s sins, but dealt with him according to his relationship with God. And consider how Jesus interacted with his disciples and with each person he encountered, according to the particulars of their situation.

All of this leads me to conclude that one end of the spectrum is not “better” or more “right” than the other. The extremes of either can be problematic (people within both cultural tendencies might find things to criticize and to try to change). But in any given culture we find ourselves experiencing as guests, we will have a better experience if we try to understand how people in that culture function, and if we try to adapt, to fit in as best we can (and this involves looking for ways that our cultural tendencies clash or are in tension with local tendencies, what is particularly “hard” for us).

In the particularist MENA region, our adaptation included developing personal relationships, and then learning how to make the most of them (I learned to always call a friend when I needed something - every Jordanian has an extensive network of cousins ready to help as needed). And learning that it goes both ways - I have to be available to help friends, to vouch for them, make connections, treat them according to our relationship, and not as somehow “neutral” or unknown.

Questions for thought:

which end of the spectrum do you tend towards?

what are some ways you have experienced the universalism / particularlism difference or tension?

Storti, Craig. Figuring Foreigners Out, 20th Anniversary Edition: Understanding The World's Cultures (p. 38). Quercus. Kindle Edition.

Note John Adams’ famous “a government of laws not of men,” which he presented as a distinctive of the system of law of the American government.

Storti, Craig. Figuring Foreigners Out, 20th Anniversary Edition: Understanding The World's Cultures (pp. 38-39). Quercus. Kindle Edition.

I would suggest that even in a universalist culture, small communities where most everyone knows each other are more likely to function in a particularist way, because things can be worked out according to the particulars of a situation, given the relational interconnections between everyone.